Blog by David Karpuk:

Unlocking the future of quantum computation:

Trust and verifiability

Early computers presented scientists with a simple dilemma: how can you trust a device whose computational abilities vastly surpass your own? Quantum computing is now approaching a similarly pivotal moment.

February 17, 2026—The advent of the digital computer provided humanity with unprecedented computational power. The first computers enabled codebreakers at Bletchley Park to help end World War II and assisted NASA in sending the first humans into space. But with the especially high stakes involved, how could scientists trust the output of these new machines? The first time we asked a digital computer to perform a calculation so large that no human could have done it with pen and paper, how did we know we got the right answer? The answer, of course, is that there were human calculators working alongside these computers that could check, using pen and paper, mechanical calculators, or slide rules that some of their calculations were correct. Provided that a computing system could pass enough such verifications, it could then be trusted to carry out calculations beyond the realm of what was humanly possible.

Here in 2026, we are at an analogous inflection point in the development of quantum computing. The first time we ask a quantum computer to perform a calculation so large that no classical computer could have done it, how will we know that we got the right answer? We won’t, unless we have a quantum algorithm which allows for classically verifiable quantum advantage. That is, we need to be able to, with only a classical computer, design an algorithm for a quantum computer to run, such that a classical computer can also verify that the output must have come from a quantum computer. For this to be the case, the quantum computer must be performing a calculation which is intractable for a classical computer. The situation today is as it was in the 50's with the first computers, with your laptop playing the role of human calculator, and the quantum computer playing the role of the first classical computers.

Charting a course towards practical quantum advantage

At QMill, as was announced in January, we have developed a classically verifiable quantum algorithm which promises to deliver this necessary step in the evolution of quantum computing. The applications for classically verifiable quantum advantage are manifold; for example, one can verify the validity of a cloud computing operator's claim of having access to a genuinely quantum computing resource. Using our quantum algorithm, verifying claims of quantumness can be in the hands of you, the user, armed only with a laptop.

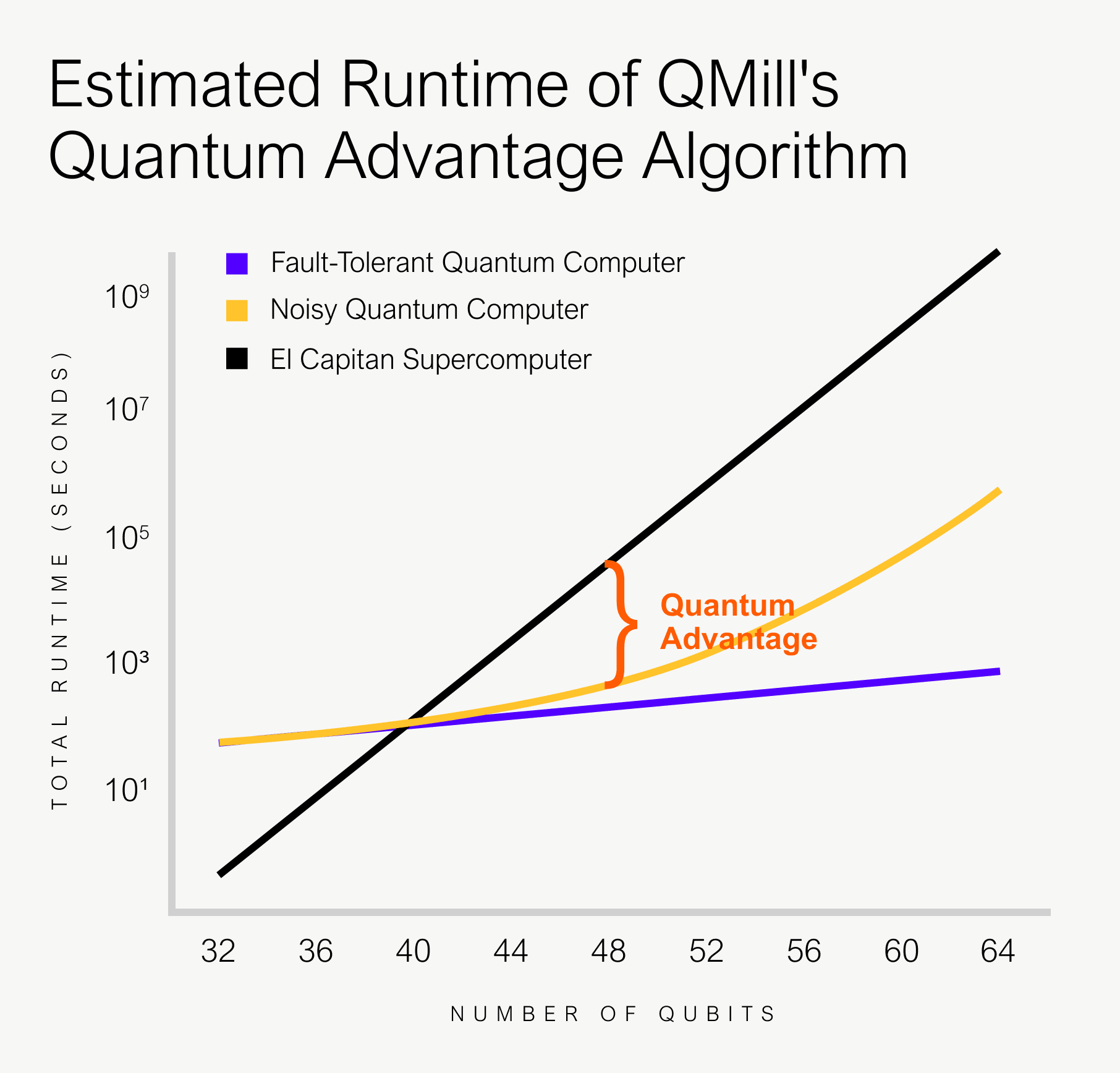

With the admittedly grandiose historical comparisons aside, what does our algorithm actually do? Well, we will be releasing a manuscript for peer review and scientific publication soon . But we can say that we expect our algorithm to achieve quantum advantage using a quantum computer with only 48 qubits and 99.94% accuracy. Here ‘advantage’ means something specific: we expect it to perform a certain computational task noticeably faster than El Capitan, the world's fastest supercomputer. All while tolerating the noise inherent in modern-day quantum computers.

Our performance estimates as of yet are just that, mathematical estimates. The algorithms team at QMill is now turning its attention towards realizing the quantum speed-up provided by our algorithm on quantum computers that exist today. Turning theory into practice is always a bit of an adventure, but we have forged a clear path towards being the first to demonstrate classically verifiable quantum advantage. And successful experimentation naturally paves the way for productization, eventually allowing our users to execute quantum algorithms with a mathematical guarantee that these computations must have happened within the world of quantum mechanics. It's indeed an exciting time to be part of our team!

Figure: The above plot depicts the estimated runtime of QMill's Quantum Advantage Algorithm on both noisy and fault-tolerate quantum computers, and compares it to the runtime it would take El Capitan, the world's most powerful supercomputer, to perform the same computational task. For our simulations, we express our circuits in the Clifford+T gate set and assume that the dominant source of error in the quantum computer is gate errors, specifically 2-qubit gate errors.

Related content:

- QMill press release (Jan 22, 2026): QMill announces a six-fold leap in reaching quantum advantage

- Video (starting at 4:20, duration 10min): Presentation by Mikko Möttönen at Cisco Quantum Summit 2026

About the author:

David Karpuk is a Principal Quantum Algorithm Engineer at QMill. Before joining QMill, he held several academic positions and worked as a data scientist. Currently he is developing the mathematics behind QMill’s practical quantum algorithms for the NISQ era.